Your saliva carries trillions of microorganisms, and new research points out that stomach viruses also use it as a mode of traveling inside your body. A mouse study from the National Institute of Health reports that viruses involved in diarrheal diseases can grow in salivary glands and spread through saliva.

Scientists have looked into how certain stomach viruses such as noroviruses and rotaviruses get to the stomach. One common way is through food or liquids contaminated with the virus’s fecal matter. But before the study’s revelations, researchers believed stomach viruses bypassed the salivary glands and targeted the intestines before exiting through feces.

The newly discovered route of transmission could explain the rapid spread of deadly viruses to billions of people each year. It also suggests that coughing, talking, sneezing, kissing, and sharing food and utensils all carry a risk of spreading viruses. The results need to be verified in human studies, however.

There is an upside to knowing the ugly truth about saliva. If scientists can learn how viruses spread, it could lead to more ways of preventing, diagnosing, and treating diseases caused by these viruses.

“This is completely new territory because these viruses were thought to only grow in the intestines,” says senior author Nihal Altan-Bonnet, Ph.D., chief of the Laboratory of Host-Pathogen Dynamics at the NHLBI. “Salivary transmission of enteric viruses is another layer of transmission we didn’t know about. It is an entirely new way of thinking about how these viruses can transmit, how they can be diagnosed, and, most importantly, how their spread might be mitigated.”

Infant mice are commonly used to study enteric viruses because their immature digestive and immune systems make them prone to stomach infections. In the current study, a group of mice less than 10 days old ate food contaminated with either norovirus or rotavirus. After one day, the researchers noticed an elevated rise in IgA antibodies in the mice’s gut. IgA antibodies are important in warding off disease, but at such a young age, infant mice should not be able to make their own antibodies.

The team also showed other unusual findings. The viruses mice were fed with had replicated at high levels in the mothers’ breast tissue. Breast milk from the mouse mothers found that the timing and levels of the IgA surge in the mothers’ milk were like the increase in IgA antibodies in the baby mice’s guts.

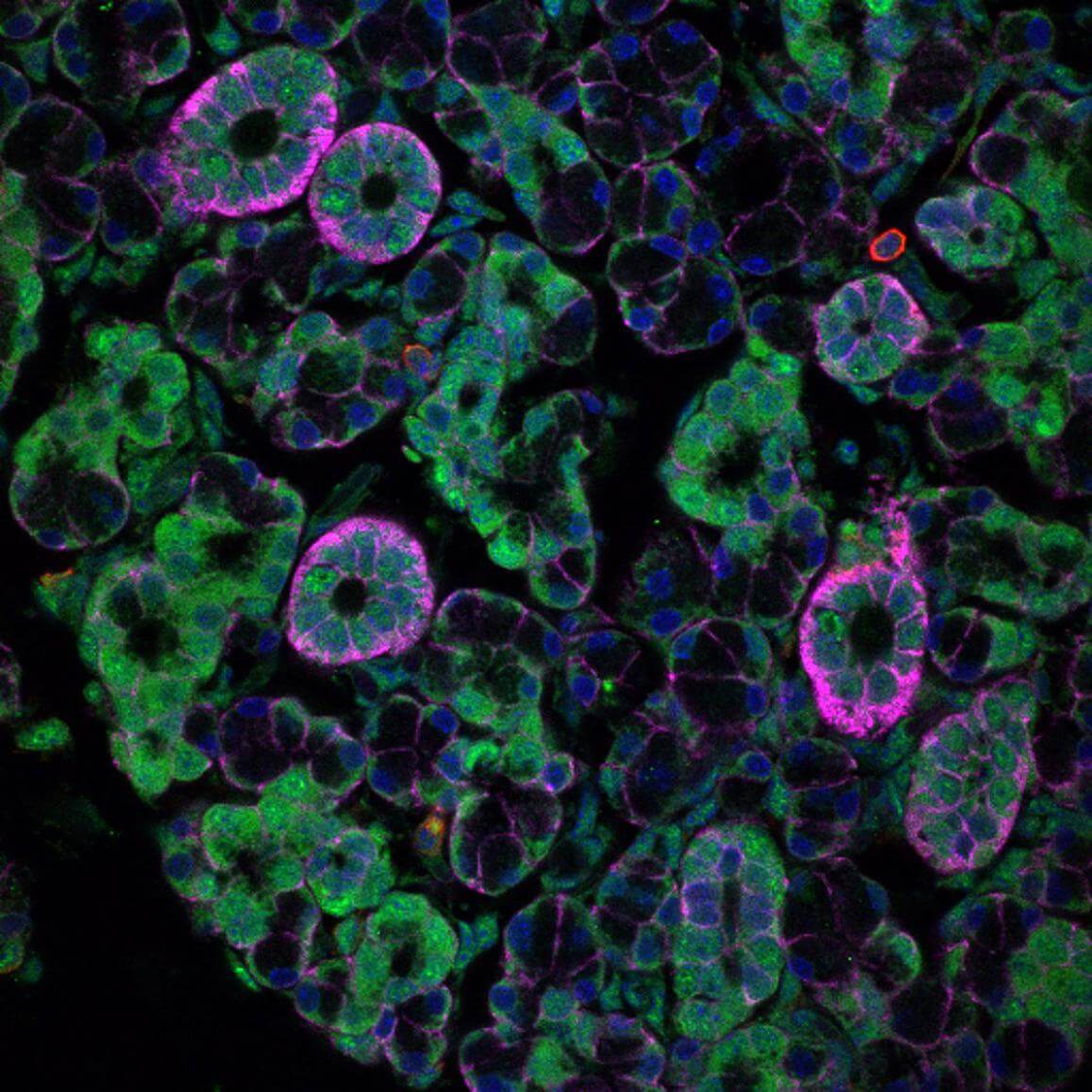

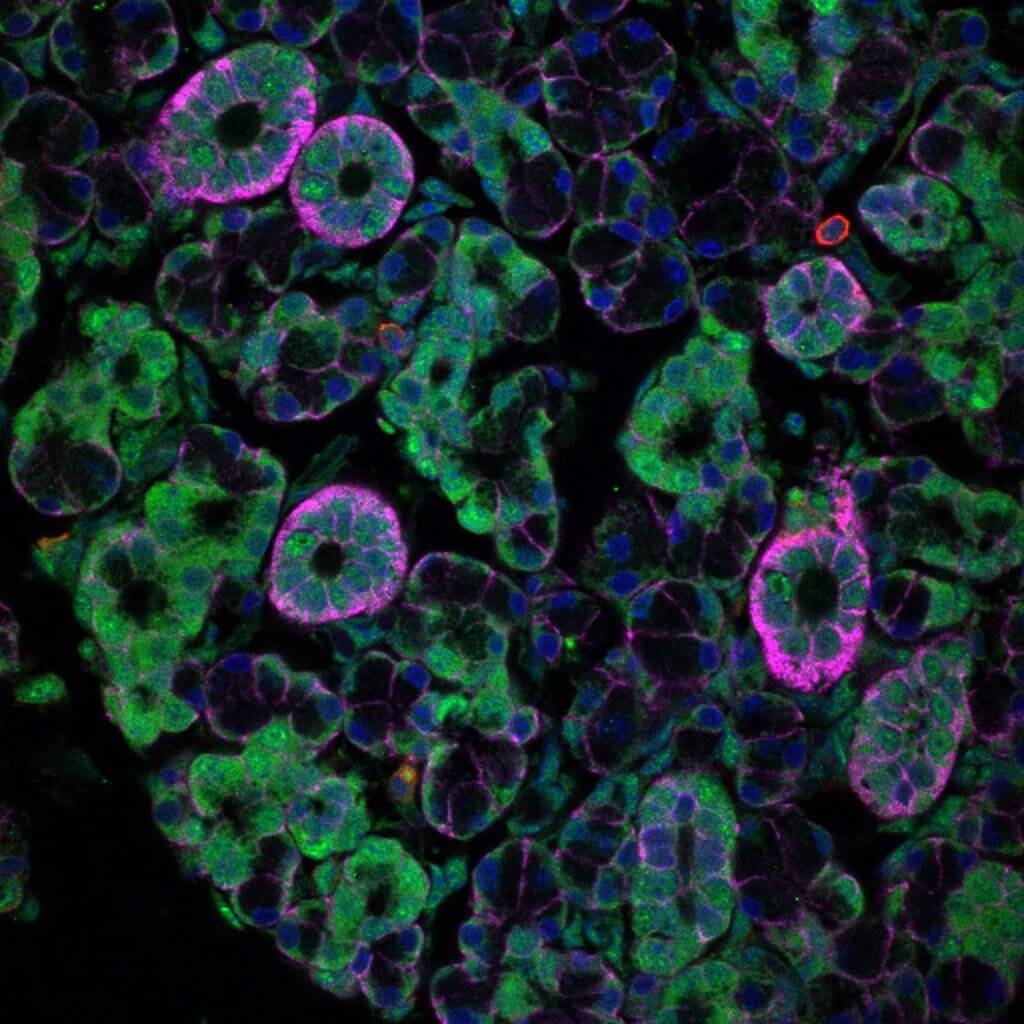

How did the virus end up at high levels in the rodent mothers’ (who were virus free at the start of the experiment) breast tissue? Further research uncovered that the viruses came not from mice leaving contaminated feces for their mothers to eat. Rather, when collecting saliva samples and salivary glands of infant mice, they found the viruses shedding and replicating in large amounts. Through breastfeeding, the viruses came from the saliva of infected mice that spread to the mother.

The study is published in the journal Nature.