One’s genetic predisposition for various tastes could lead to ‘personalized diets’ aimed to improve longterm health

Order the extra-large pizza. Pile on heaps of mozzarella. Double the Italian sausage, layer on about a pound of bacon (real bacon, not that round stuff.) There’s no room left for the peppers and mushrooms but add some red onions. No pineapple – on pizza it’s an aberration. Put on a bib and keep a stack of napkins within reach. Then, your genes compel you to devour it with abandon – the compulsion must be satisfied! No guilt allowed. Your response is not your fault (said facetiously) – it’s in your DNA.

Findings of a new study, released by scientists at Tufts University in Boston, reveal that genes affecting taste influence food choices. That means that those genes will ultimately influence cardiovascular and metabolic health. That pizza just may coat the inside of your arteries, significantly increasing your risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) and strokes.

It may be that taste perception (sweet, salt, sour, bitter, and savory) should be considered in the tailoring of a personalized diet for individuals. The goal is reducing risk for diet-related chronic diseases, such as Type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases.

“We know that taste is one of the fundamental drivers of what we choose to eat, and, by extension, our diet quality,” says Julie E. Gervis, of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts. “Considering taste perception could help make personalized nutrition guidance more effective by identifying drivers of poor food choices and helping people learn how to minimize their influence.”

For example, someone with strong bitter taste perception tends to eat fewer cruciferous vegetables. Choosing different vegetables more palatable to the patient may be recommended. “Most people likely don’t know why they make certain food choices,” says Gervis. “This approach could provide them with guidance that would allow them to gain more control.”

Previous studies have looked at genetic factors related to single tastes in certain groups of people. The new study is unique in that it examines all five basic tastes, across a more diverse sample of adults. It is also the first study addressing whether genetic factors for taste perception are associated with choosing particular food groups and with assessing risk for cardiovascular and metabolic disease.

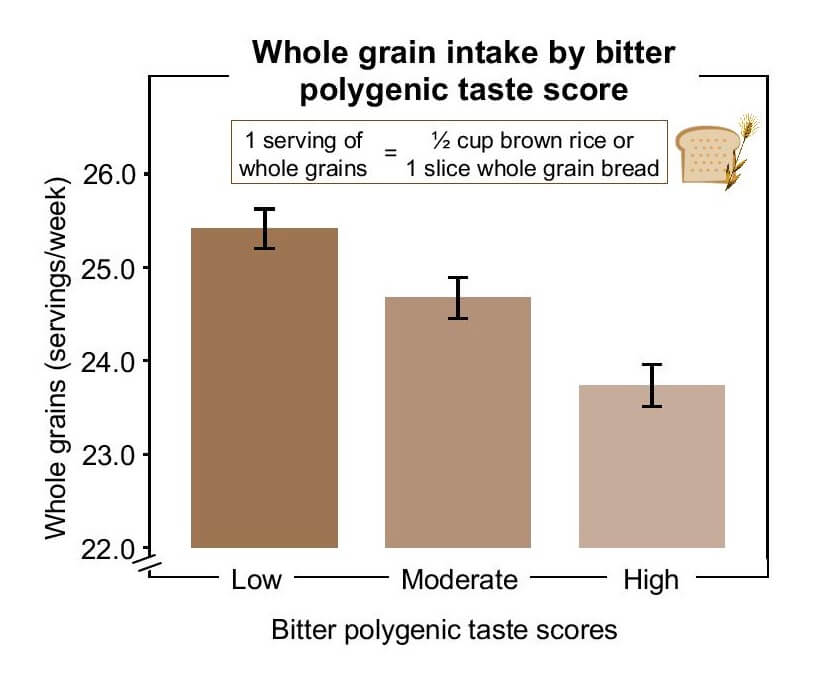

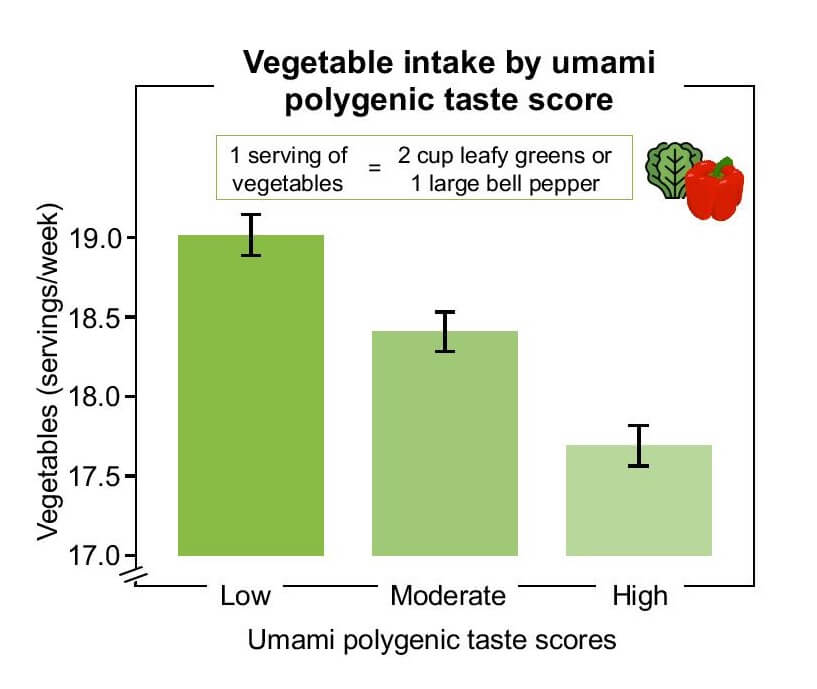

The scientists used data from previous research to develop a “polygenic taste score” which estimates the cumulative effect of many genetic variants affecting taste perception. A higher polygenic taste score for sweet means that a person has a greater genetic tendency to perceive sweet tastes.

Study authors analyzed the polygenic taste scores, along with diet quality and cardiometabolic risk factors of 6,230 adults. Risk factors included waist size, blood pressure, serum glucose, triglycerides, and cholesterol.

The analysis identifies certain associations between taste-related genes with food groups and cardiometabolic risk factors. Data shows that genes related to bitter and savory tastes affect diet quality by influencing food choices, while genes related to sweet taste are more influential on cardiometabolic health.

Researchers say that participants with a greater bitter polygenic taste score ate fewer whole grains, compared to participants with a lesser bitter polygenic taste score. A greater savory polygenic taste score was associated with eating fewer vegetables. A greater sweet polygenic taste score was associated with lower triglyceride concentrations.

The researchers caution against generalizing these findings to everyone. “However, our results do suggest the importance of looking at multiple tastes and food groups when investigating the determinants of eating behaviors,” says Gervis. “It will be important to replicate these findings in different groups of people, so that we can understand the bigger picture and better determine how to use this information to devise personalized dietary advice.”

Please note: Diet soda does not cancel out the indiscretion of a decadent pizza.

Gervis presented the team’s findings at NUTRITION 2022 LIVE ONLINE, the flagship annual meeting of the American Society for Nutrition.