Malignant melanoma is the most deadly skin cancer, and the fifth most common cancer. Immunotherapy – a treatment that helps the patient’s immune system kill cancer cells – is a treatment of great interest and active research. Research shows that there is a link between a patient’s individual gut microbiome and the patient’s response to immunotherapy.

Several microorganisms have been identified as having a favorable effect on response to immunotherapy. A new study suggests that microorganisms which hinder the response to immunotherapy may have greater influence than beneficial microorganisms.

These are the findings of collaboration among researchers at Oregon State University, the National Cancer Institute, the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, and the University of Pittsburgh.

According to Andry Morgun, of the Oregon State University College of Pharmacy, the research is a significant step forward in the treatment of various types of cancer, including melanoma. “Our findings shed new light on the highly complicated interaction between the gut microbiome and immunotherapy. It can set a course for future studies,” Morgun says in a statement.

About 100,000 cases of malignant melanoma are diagnosed per year in the United States. Of those patients, about 7,000 deaths are expected. It is one of the most aggressive cancers, rapidly metastasizing to organs throughout the body.

The new study, published in Nature Medicine, uses a technique called immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). It relies on inhibitor drugs that block proteins produced by some immune system cells and some cancer cells. The proteins, called checkpoints, prevent an immune response from being too strong. When the checkpoints are blocked, T cells are more affective at killing cancer cells. The ICB technique is becoming a “game-changer” in the successful treatment of malignant melanoma and a variety of other cancers.

The researchers used a particular ICB with a computer modeling technique called transkingdom network analysis. It was invented by Morgun and Natalia Shulzhenko, of the Oregon State’s Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine. It was used to determine which bacteria were associated with more or less favorable responses to treatment.

The results of their research also suggested that about a year after treatment began, it was the gut microbiome that became the dominant factor in the patients’ response to therapy. The researchers reported that the microorganisms that detracted from therapy had a greater role than did the bacteria that enhanced therapy.

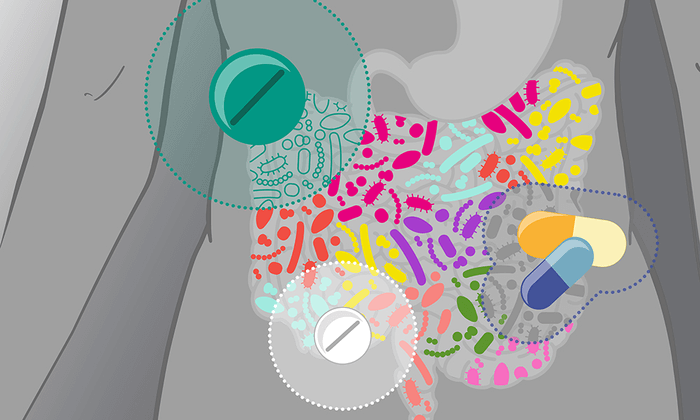

Many studies have been done which show that a patient’s individual microbiome has a role in how the body responds to immunotherapy. The human microbiome consists of more than 10 trillion microorganisms. There are about 1,000 species of bacteria in the microbiome (Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum, Roseburia spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila were associated with a better immune response.)