Sometimes we treat our stomachs as though they are indestructible. Venture out to the annual Iowa State Fair, and you can treat yourself to some famous (or infamous, depending on your perspective) food on a stick. You could try the Icelandic fermented shark on a stick. For dessert, there’s pecan pie — deep fried on a stick — topped with caramel and bacon! Fortunately, we have glial cells in our body’s second brain, the gut’s own nervous system. Just one of its growing list of functions is helping to maintain a healthy intestine, no matter what you choose to fill your stomach with.

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute in London found that glial cells also coordinate immune responses of the gut following pathogen invasion or insult to the tissues. The glial cells could be key targets when exploring new treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Maintaining a healthy gastrointestinal (GI) system and repairing tissue after infection or injury is a complex process. If that process goes awry, it can lead to IBD, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Previous research in IBD focused on the activity of various immune cells. Mysteries remain, however, suggesting that other cells may play a critical role in the disease’s pathology. To address these mysteries, researchers studied the role of enteric glial cells in response to tissue damage.

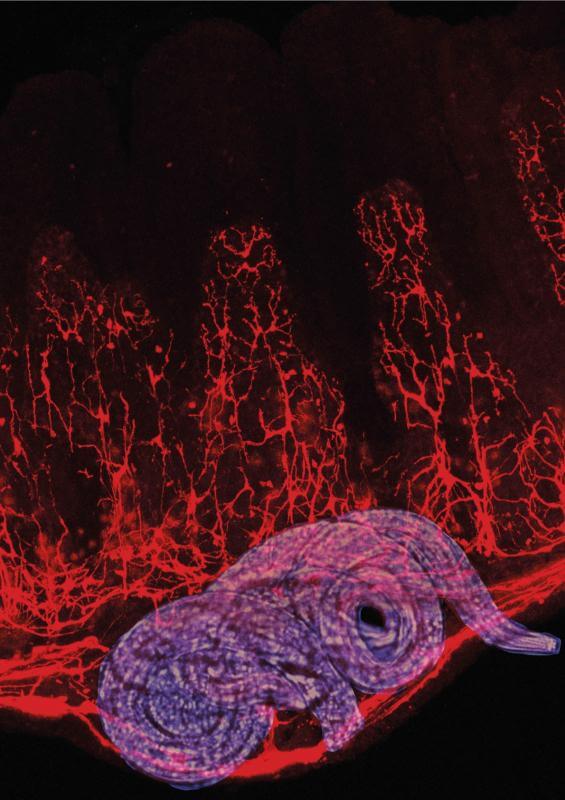

The scientists infected mice with a common roundworm parasite, Heligmosomoides polygyrus. When the parasite invades the gut wall, a protein, called interferon gamma, is quickly released by immune cells. They discovered that one of the protein’s first targets was the nearby glial cells. The protein-activated glial cells released signals that attracted other immune cells to the damaged sites, to fight infection and repair tissue damage.

The researchers asked if similar mechanisms were present in humans. They analyzed data, previously collected by others, of colon samples from people with ulcerative colitis. The disorder is a chronic condition in which the colon and rectum become inflamed, causing severe diarrhea and stomach cramping. It takes a significant toll on quality of life.

As seen in the mouse cells, interferon gamma targeted human glial cells, indicating that glial cells in the human gut have a role in inflammatory conditions of the bowel.

“Sadly, currently treatments for inflammatory bowel disease are often limited to alleviating the symptoms, rather than tackling the cause,” says Fränze Progatzky, a scientist with the Crick Institute’s Development and Homeostasis of the Nervous System Lab, in a statement. “Our insights into the importance of enteric glial cells in maintaining a healthy intestine open the door to further studies into how these cells work and interact with the immune system, and in the future could help us develop new treatments for these (IBD) conditions.”

The team also studied the role of glial cells in maintaining healthy gut tissues in the absence of infection or injury. They found that the glial cells are important to regulating the wellbeing of the GI tract, in addition to the cells’ roles in tissue insult and infection.

“Glial cells are present in many organs, and so it’s possible they also play similar roles in maintaining healthy tissue and mounting appropriate responses to pathogens or toxins in other parts of the body,” says Vassilis Pachnis, leader of the Development and Homeostasis of the Nervous System Lab. “It will be exciting to explore this possibility further.”

The original study is published in Nature.