Penicillin (PCN) was discovered by “accident.” Some mold landed on the Petri dishes growing germs in Alexander Fleming’s lab. Where the mold landed, germs would die. It saved countless troops in WWII – 2.4 million doses went to the invasion of Normandy. Recently, another “accident” led to a discovery – a previously unknown type of cell death that happens in the guts of the common fruit fly. Researchers named the process “erebosis.” It seems to play a role in gut metabolism. The newly discovered process demands a revision of the conventional concept of cell death.

A research group led by Sa Kan Yoo at the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research (BDR) were studying a fruit fly version of ANCE, an enzyme that lowers blood pressure. So how did the team stumble upon their discovery? “We found that ANCE labels some weird cells in the fruit fly gut, but it took a long time for us to figure out that these weird cells were actually dying,” Yoo explains in a statement.

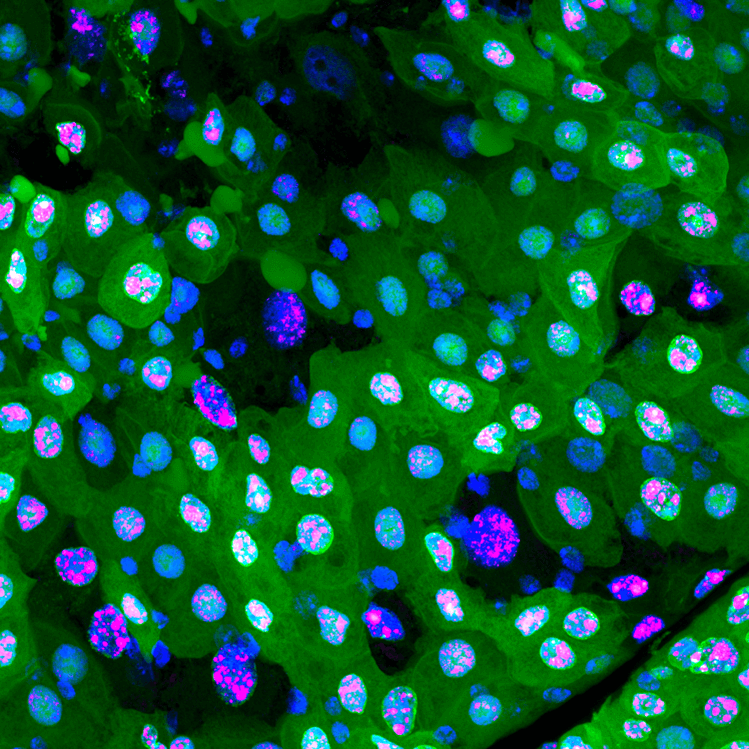

Scientists found that the strange cells were dark, lacking nuclear membranes, mitochondria, and cytoskeletons, and sometimes even DNA and other cellular items that are needed for cells to stay alive.

The new process was so gradual, and unlike the familiar sudden and explosive cell death called apoptosis, that they realized it might be something new. They theorized that the new type of cell death is related to cell turnover in the intestines. They tentatively named the process erebosis, based on the Greek “erebos,” meaning “darkness.” That’s because the dying cells looked so dark under the microscope.

The dying cells did not show any of the molecular markers for apoptosis. Cells in late-stage erebosis did show a general marker for cell death related to degraded DNA. Detailed examination of the cells in which erebosis was occurring revealed that they were located near clusters of gut stem cells. This is good evidence erebotic cells are replaced by newly differentiated gut cells during turnover.

Ironically, the enzyme that led to this discovery does not seem to be directly involved in the process, as knocking down or overexpressing ANCE did not affect turnover or erebosis.

“I feel our results have the potential to be a seminal finding. Personally, this work is the most groundbreaking research I have ever done in my life.” says Yoo, “We are keenly interested in whether erebosis exists in the human gut as well as in fruit flies.”

The study is published in the open access journal PLoS Biology.